This article by Edwin G. Pulleyblank on Chinese-Iranian relations was originally published in the Encyclopedia Iranica on December 15, 1991 and last updated on October 14, 2011. This article is also available in print (Vol. V, Fasc. 4, pp. 424-431).

The version printed below is different in that it has embedded photographs and captions used in Kaveh Farrokh’’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division and were also presented at Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006.

=============================================

Contact between China and Iran was initiated toward the end of the 2nd century B.C.E. by the envoy Chang Ch’ien (Zhang Qian), who journeyed to the west in search of the Yüeh-chih (Yue-zhi), a people that had migrated from the borders of China after having been defeated by the Hsiung-nu (Xiongnu). The Chinese hoped to enlist the Yüeh-chih as allies against this common enemy. It is, of course, possible that there had been indirect contacts even earlier. Speculations about possible western influences on Chinese astronomy, geography, myth, and folklore in pre-Han times, presumably through Iranian intermediaries (see, e.g., Maspéro, 1955, pp. 505-15), remain unsubstantiated by firm evidence, however.

![]()

The Terracotta army In the north-west Chinese region of Xian (left) at the mausoleum of China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang (right), who died more than 2,200 years ago. The tomb contains approximately 8,000 life-sized terracotta warriors and horses. Qin Shi Huang unified China, built China’s first Great Wall and constructed a city-sized mausoleum along with a massive Terracotta Army by utilizing 700,000 laborers. Chinese archaeologists have unearthed evidence that a foreign worker helped build the Terracotta Army mausoleum. Remains of the worker, described as a “foreign man in his 20s”, found among 121 skeletons in workers’ tomb 500 meters from mausoleum (as reported by the State-run Xinhua news agency). DNA tests were used to identify the ethnicity of 15 workers Tan Jingze, an anthropologist with Fudan University, told Xinhua that “One sample has typical DNA features commonly owned by the Parsi [Zoroastrians]… the Kurds…and the Persians in Iran,” [i.e. all from the Iranian stock] (Picture and caption from Kaveh Farrokh’’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division and were also presented at Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006).

It has long been recognized that the Yüeh-chih must correspond, wholly or in part, to the Tochari, Asii (or Asiani), and Sacaraucae, who, according to Strabo (11.8.2), overthrew the Greek kingdom of Bactria, thus providing the earliest synchronism between Chinese and western historical records. Chang Ch’ien found them on the northern bank of the Oxus, but they were already overlords of Ta-hsia (Daxia), the name by which he called Bactria. He did not succeed in his mission to persuade them to return and join with the Chinese against the Hsiung-nu, but he brought back news not only of the countries that he had visited in person but also of more distant lands (see ch’ien han shu). His descriptions of these countries provide glimpses of contemporary life in the Iranian city-states, some of which are mentioned by name. In western Turkestan the dominant powers were the Ta-yüan (Dayuan; transcription of *Taxwar?) in Sogdiana and the K’angchü (Kang-ju), with Tashkent as their capital. It is probable that, like the Yüeh-chih, both peoples were nomadic invaders from farther east who spoke languages related to Tokharian (Pulleyblank, 1966). The major power in Persia was Parthia, which Chang Ch’ien called An-hsi (q.v.; An-xi = Aršak).

![]()

Iranian engineers supervising the construction of the Persepolis palace circa 2400-2500 years ago. A number of Chinese archaeologists now state that contacts between Iranian peoples and Far East began a century earlier than believed. Iranian craftsmen of the Persepolis tradition were present in Qin China; earlier studies suggested first contact occurring later during Han dynasty (206 BC-220 CE) (Picture and caption from Kaveh Farrokh’’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Divisionand were also presented at Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006).

Chang Ch’ien’s report inaugurated a period of intense diplomatic activity and the development of trade relations via the so-called Silk Road across Inner Asia, which in succeeding centuries had a profound impact on both China and the Iranian peoples, unfortunately too little documented in written records. Under the Han dynasty (Former, or Western, Han, 206 b.c.e.-23 c.e.; Later, or Eastern, Han, 25-220 c.e.) embassies were exchanged with Parthia around 106 b.c.e. and again at the end of the 1st century c.e. In the 1st century b.c.e., after the Chinese had succeeded in displacing the nomadic Hsiung-nu as overlords of the Tarim basin, the easternmost Iranian city-states, Khotan (Yü-t’ien/Yu-tian), Kashgar (Shu-le/Shu-le), and Yarkand (So-chü/Suo-ju; see chinese turkestan i. in pre-islamic times), enjoyed particularly close contacts with China. These relations were interrupted during the civil wars toward the end of the Former Han Dynasty, at the beginning of the 1st century c.e., but were restored a few years later; they then lasted more or less unbroken until the renewed civil war and Chinese withdrawal from the west after the Taoist Yellow Turban uprising of 184, which helped to bring down the Later Han dynasty (see, e.g., Mansvelt Beck, pp. 317-57).

The Yüeh-chih and the Kushans

Shortly after Chang Ch’ien’s visit the Yüeh-chih crossed the Oxus and carved out a kingdom for themselves in Bactria (q.v.). In the 1st-2nd centuries c.e., under the rule of the Kushan dynasty, they extended their power south across the Hindu Kush and east into Gandhara and northern India. In the process they gave up their nomadic way of life and adopted the mixed Hellenized Iranian and Buddhist Indian civilization of their settled subjects (see, e.g., Bivar, pp. 191-94; Frye, pp. 191-95); in fact, the Kushan empire became the main center from which Buddhism (q.v.) was introduced to the Far East (see below). There is also evidence that toward the end of the 2nd century the Kushans extended their power north of the Oxus and east into the Tarim basin as far as Lou-lan, near the area from which they had migrated westward nearly 400 years before. Although there is no explicit record of such a Kushan occupation in Chinese sources, presumably because the Chinese were preoccupied with their own internal troubles, it left traces in the use of Gandhari Prakrit written in Kharoṣṭhī script, which remained the administrative language in the local kingdom of Lou-lan in the following century (Brough). An independent embassy from Khotan visited the Han court in 202, which suggests that by then the Kushans had withdrawn west of the Pamirs (Pulleyblank, 1969). In 230 an embassy was sent by the Kushan king Po-t’iao (Bo-tiao = Vāsudeva) to the court of Wei (220-65), which had replaced the Han dynasty in northern China (Pulleyblank, 1969). There is no further Chinese reference to the Kushans after this embassy, presumably because their territory was conquered shortly afterward by the Sasanian dynasty of Persia, an event that went unnoticed in Chinese sources (Brough; Pulleyblank, 1969).

At the state level Chinese contacts with western countries in the next three and a half centuries were sporadic. After the Western Chin (Jin) dynasty (265-317) had succeeded the Wei in northern China embassies arrived from the K’ang-chü and the Ta-yüan in the period 265-74 and in 285 respectively, but the accounts of their lands in the Chin shu, which was compiled only much later, merely repeated information from earlier sources. Shortly afterward, in 304, non-Chinese tribesmen who had been allowed to settle inside the northern frontier during the Later Han period forced the Chin to withdraw south of the Yangtze river; according to the evidence from Chinese records, there were no further diplomatic missions to and from western countries until the mid-5th century, after the T’o-pa (To-ba, or Northern) Wei (386-535) had managed to reunite northern China. Contacts were made with the outer Iranian states in the Tarim basin, Sogdiana, and Afghanistan, which by that time had come under the domination of new nomadic powers, the Chionites (q.v.) and the Hephthalites (see, e.g., Frye, pp. 346-51).

Embassies from Po-ssu (Bo-si; Mathews, nos. 5314, 5574), the name by which the Chinese referred to Sasanian Persia, arrived at the Northern Wei court ten times between 455 and 522 (Ecsedy). The embassy of 518 brought a letter from the Persian king Chü-he-to (Ju-he-duo; Mathews, nos. 1535, 2115, 6416; Early Middle Chinese kɨa-γwa-ta), that is, Kavād I (488-96, 498-531). The contemporary southern dynasty, Liang (502-57), received Persian embassies in 533 and 535. Western Wei (535-57), which succeeded to one part of the territory of Northern Wei, received a Persian embassy in 555 (Ecsedy). The reunification of the whole of China by Yang Chien in 589 led to renewed diplomatic initiatives under the Sui dynasty (581-618). The second emperor, Yang-ti (605-17), sent an embassy to Ḵosrow II (590, 591-628), which elicited a reciprocal embassy from Persia to China (Sui shu 83). The accounts of Persia in several pre-T’ang dynastic histories, the Wei shu (history of the Wei dynasty), Liang shu (history of the Liang dynasty), Pei Chou shu (history of the Northern Chou dynasty), Sui shu (history of the Sui dynasty), Nan shih (history of the southern dynasties), and Pei shih (history of the northern dynasties), contain information that had no doubt been gained from these embassies. Unfortunately, the textual relationships among these various sources, which, except for the Wei shu, were all compiled in the early T’ang period (618-907) from earlier materials, pose a complex problem (see Miller, pp. 47ff.). The original account in the Wei shu has been lost, though at least part of it was copied into the Pei shih, from which the extant text of the Wei shu has been restored. A later encyclopedic work, the T’ung-tien, also contains versions of the same information, and some of it is repeated in the Chiu T’ang shu and Hsin T’ang shu (old and new (histories of the T’ang dynasty; translations of the relevant passages are found in Chavannes, 1903; see pp. 99-100 on the sources).

More intimate relations between China and the Persian kings came about in the early years of the T’ang dynasty (618-907). The last Sasanian ruler, Yazdegerd III (632-51; Yi-si-si, Chavannes, index, p. 331), who was hard pressed first by the western Turks on his eastern flank and then by the Arabs in the west, sent an embassy to China in 638. After he was killed in 31/651 his son Pērōz (Bi-lu-si, Chavannes, index, p. 353) took refuge in Ṭoḵārestān, where he obtained the support of the local Turkish ruler and sent an embassy to China asking for assistance. No help was forthcoming, but after the Chinese defeat of the western Turks in 659, when a short-lived administration was set up in the conquered territory, Pērōz was recognized as governor of Po-ssu, with his capital at Ji-ling (Zarang, in Sīstān). He was unable to hold out against the advancing Arabs, however, and took refuge at the T’ang court between 670 and 673. After the death of Pērōz his son, called Ni-nie-shih (Chavannes, index, p. 349) in Chinese, was escorted to the west by Chinese troops and remained there under the protection of the Turkish ruler of Ṭoḵārestān for about twenty years before returning to die in the Chinese capital sometime between 707 and 709. From then until the battle of Talas (Ṭarāz) in 751, which established Arab dominance in Transoxania (Ebn al-Aṯīr, V, p. 449; Chavannes, 1903, pp. 143, 152-53; Barthold, pp. 195-96; see chinese turkestan ii. in pre-islamic times), regular embassies from Po-ssu to the T’ang court were recorded (Chavannes, 1903, pp. 171-73). Presumably at that period the name Po-ssu referred to a puppet kingdom on the eastern borders of Afghanistan, maintained by the Turkish rulers of Ṭoḵārestān. All trace of this kingdom disappeared after the battle of Talas and the An Lu-shan rebellion in China in 755, though there is evidence that descendants of refugees from the Sasanian empire were still serving as soldiers at Ch’ang-an, the Chinese capital, in the 9th century (Harmatta, 1971).

Trade relations

Even less well documented than official diplomatic contacts between China and Iran are the trade relations that developed between these two great civilizations after the Chinese opening to the west in the 2nd century b.c.e. The diplomatic missions actually played an integral part in these trade relations, not only because of the “tribute” that they brought to the Chinese court and the “gifts” that were bestowed in exchange, but also because of the private trade that was permitted after the formal courtesies had been exchanged. On the Chinese side profitable trade with the newly discovered west was an important stimulus for diplomatic activities. In the first flush of enthusiasm that followed Chang Ch’ien’s return from Sogdiana there was eager competition among “sons of poor families” to take part in missions to the west for the sake of the trading opportunities that they afforded, and under the Han Chinese merchants were at times directly involved in military operations to gain control of the Western Regions of the country (Yü, 1967, pp. 137-38). In the end, however, foreigners, especially Iranians, were predominant in promoting and controlling the overland trade from China across Central Asia.

![]()

A Chinese Ewer of Sassanian inspiration (6th-7th Centuries CE) (Picture and caption from Kaveh Farrokh’’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division and were also presented at Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006).

From the beginning Chinese silk was the most important commodity in this trade, so much so that Seres, “the silk (people),” was the name by which the Chinese were first known to the Greeks. Silk was much sought after both in the Roman empire and in India and presumably also in Iran. The importance of Iranians in the silk trade, however, lay more in their role as middlemen than as consumers. When Kan Ying (Gan Ying) was sent by Pan Ch’ao (Ban Chao), protector-general of the Western Regions, as envoy to Ta Ch’in (Da-qin, i.e., the Roman empire) in 97 c.e., he went only as far as the Persian Gulf, where he was induced to turn back by sailors from Parthia, who told exaggerated stories about the length and difficulty of the journey (Chavannes, 1907, pp. 177-78). Possibly local merchants viewed the establishment of direct contacts between China and Rome as a threat to their own monopoly. The wish to circumvent this Parthian monopoly may also have been a factor encouraging the opening of a sea route between China and India; such sea trade had already begun by the end of the 1st century b.c.e. and gradually increased during the next few centuries (see below).

The large quantities of Sasanian coins discovered on Chinese territory are evidence of the continued importance of Iran in China’s western trade after the Sasanians had supplanted the Parthians in Persia. The coins of twelve different rulers, from Šāpūr II (310-79) to Yazdegerd III have been recovered, some along the Silk Road in Sinkiang (Xin-jiang) but others at Hsi-an, Lo-yang, and many other places in China proper (Hsia, 1974).

It was not the inhabitants of Persia, however, but rather the Sogdians who played the key role in the overland trade between China and the west in pre-Islamic times. A cache of manuscripts in Sogdian language discovered by M. A. Stein at a post on the Chinese northwestern frontier near Tun-huang (Dun-huang) has provided striking evidence of Sogdian preeminence at an early date. The letters turned out to have been written by Sogdian merchants to their home bases (See ancient letters). Beside personal news of family and friends, the letters include information about the latest commodity prices and rates of exchange for silver, as well as about difficulties in postal communications. One of them also tells of recent sensational events in China: the departure of the emperor from his capital at Lo-yang because of famine, the subsequent burning of the palace and abandonment of the city, and the capture of the cities of Yeh and Ch’ang-an by hostile forces that included Xwn (i.e., Hūn = Hsiung-nu). W. B. Henning (1948) concluded that the letter referred to events of 311-13 that were connected with the fall of the Western Chin. J. Harmatta (1979) argued, on the contrary, that the report corresponds better to events of the years 190-93, during the civil wars at the end of Eastern Han. His specific dating to the year 196 depends, however, on a highly questionable interpretation of the date formula at the end of the letter, and the new identifications of place names that he proposed are also in doubt. Recently Frantz Grenet and Nicholas Sims-Williams have proved Henning’s date correct, thus providing incontrovertible evidence that in the early 4th century Sogdian merchant houses had agents at Tun-huang on the western frontier of China, as well as at the capital, Lo-yang, and other cities in the interior.

![]()

A map of ancient Chang’An in northern China (left) and the remains of that city (right). This ancient Chinese metropolis boasted up to a million residents. Iranian refugees from post-Sassanian Iran were often settled in the Western Market area southwest of the imperial palace. The city also boasted a Sassanian Zoroastrian temple at Hsien-tz’u: a, a Manichean church at Ta-yun Kuang-ming Ssu and a Nestorian church at Ta-ch’in Ssu (Picture and caption from Kaveh Farrokh’’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division and were also presented at Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006).

Although silk was the most important commodity in the trade between China and the west, many other products were also exchanged. The Sogdian letters mention, in addition to various kinds of silk, textiles of hemp, blankets or carpets, perfumes, musk, rice wine, camphor, fragrant resins, drugs, and similar items (Harmatta, 1979, p. 165). The many western products, especially plants, that were introduced to China from Iran or through Iranian intermediaries were the subject of a classic study by Berthold Laufer (Sino-Iranica).

Although no later records comparable to the Sogdian letters have so far been discovered, there is abundant evidence of other kinds that Sogdian involvement in the China trade continued unabated in the following centuries. In Sui and T’ang times the Hu, or Sogdian, merchant not only was mentioned frequently in official historical sources but also had become a commonplace figure in popular literature, most often as a connoisseur of precious gems (Schafer, 1951, pp. 414-15). There were sizable colonies of these foreigners not only in the oases of Kansu, along the western part of the trade route, and at the capital cities of Ch’ang-an and Lo-yang but also at major inland centers like Yang Chou, the entrepôt at the southern end of the transport canal joining the Yellow river to the Yangtze, where several thousand merchant Hu were massacred by rebel soldiers in 760 (Schafer, 1963, p. 18).

Sogdians who settled in China or had dealings with China are recognizable from the characteristic Chinese surnames that they adopted. For example, K’ang was abbreviated from K’ang-chü (attested, e.g., in Jiu Tang shu, tr. Chavannes, 1903, p. 26), though it referred in Sui and T’ang times to Samarkand, rather than Tashkent (e.g., in Tang shu, tr. Chavannes,1903, p. 132 and n. 5). An was originally an abbreviation of An-hsi (i.e., Aršak), the Chinese name for Parthia, but was later applied to Bukhara; Shih (Early Middle Chinese dźiajk) “stone” (Mathews, no. 5813) referred to Tashkent, lit. “stone city,” which was probably a translation into Turkish of a much earlier name (Pulleyblank, 1962, pp. 246-48; Aalto, 1977). Shih (lit. “history,” Mathews, no. 5769; Early Middle Chinese ṣɨʾ) referred to Kish (Šahr-e Sabz, modern Shahr in Uzbekistan), Mi (lit. “rice,” Mathews, no. 4446) to Māymarḡ, Ts’ao (Mathews, no. 6733) to Kabūdan, Ho (Mathews, no. 2109) to Kūšānīya, and Huo-xün (Mathews, no. 2395, 2744) to Ḵᵛārazm (cf. Chavannes, pp. 132-49). These surnames were particularly common in the T’ang period, sometimes clearly referring to recent arrivals from Central Asia, sometimes to families that had been living as foreigners in China for some time, sometimes to people who had become fully assimilated and indistinguishable from the rest of the population.

![]()

Tse-Niao (Bird) motif mural painting in Kizil, Sinkiang, 6-7th Centuries AD. (left) and a Pheasant as depicted in late Sassanian arts 6-7th Centuries AD (Picture and caption from Kaveh Farrokh’’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division and were also presented at Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006).

There was a great vogue, especially in the first half of the eighth century, for Iranian objects and customs of all kinds: foodstuffs, clothing, furniture, music, and dancing (Hsiang). Although Iranian influence on the Chinese visual arts lies outside the scope of this article (see xi, xii, below), representations of Central Asians among the T’ang tomb figurines should be mentioned as vivid illustrations of the cosmopolitan character of Chinese culture at that period.

Sogdians among the nomads

The word hu, which under the Han had been a general term for the nomadic horsemen of the north, especially the Hsiung-nu, came to refer to westerners from Central Asia, especially Sogdians, somewhat later. This change poses an interesting problem that has never been clearly explained. Probably it occurred during the 4th century, when northern China was overrun by the so-called Five Barbarians (wu hu), a conventional list comprising Hsiung-nu, Chieh, Hsien-pei, Ti, and Ch’iang peoples, from which arose one or more of the short-lived dynasties known as the Sixteen Kingdoms. The second of these peoples, the Chieh, were considered a branch of the Hsiung-nu, but, though they had entered China as subjects of the Hsiung-nu, they were racially distinct and had connections with K’ang-chü, that is, the Tashkent region (Pulleyblank, 1962, pp. 246-48). The Chieh or Chieh-hu were known for their “high noses and deep eyes,” which set them apart not only from the Chinese but also from other non-Chinese, and it was perhaps these features, often mentioned, that led to the specialized application of the more general term hu to the Iranians of western Turkestan. At least two of the typical Sogdian surnames were already found among the Chieh or Chieh-hu who participated in the barbarian uprisings of the 4th century. The more prominent was Shih, the surname of Shih Le, who founded the Later Chao kingdom in 319. K’ang, which in one document was explicitly qualified as Su-t’e (< *Soγ’ak), was the name of a prominent clan at Lan-t’ien in present Shensi province and was attested elsewhere as well (T’ang, p. 421).

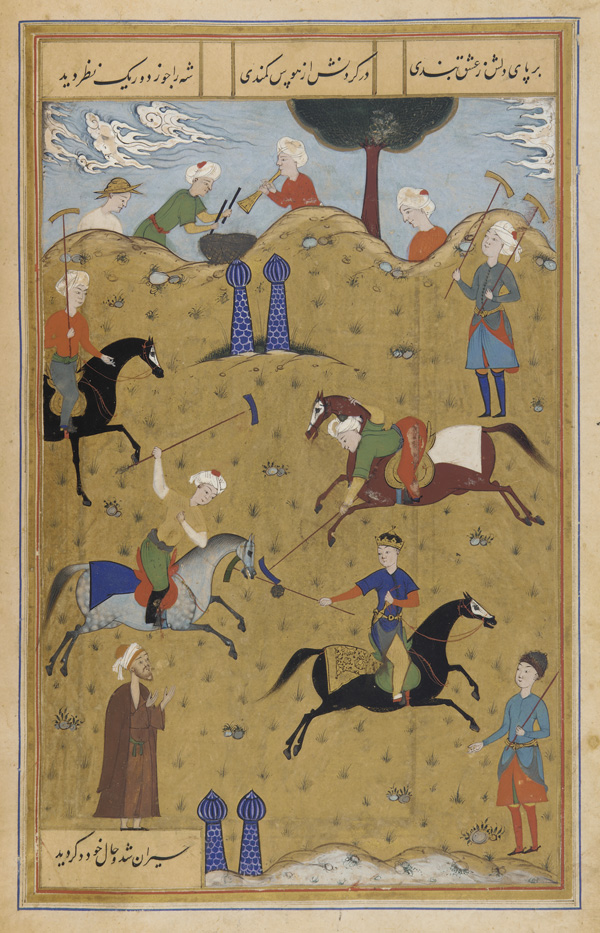

![]()

The procession of the ambassadors painting at Afrasiab (Source: Faqsci in Public Domain); this painting is believed to have been commissioned sometime in 650 CE by Varkhuman, the king of Samarkand.

The Iranians present among the subject peoples of the Hsiung-nu who settled in Han China must have been slaves taken by the nomads through conquest, but it is not clear whether at this early date there was already a desire to make use of the skills of oasis dwellers in order to profit from the trade between China and the west. Nor is it clear whether these Iranians maintained contact with their original homeland or with the Sogdian merchants who came to China independently, seeking profits, or whether the Sogdian merchants themselves sought to influence their nomadic overlords to protect the trade routes. There is, however, good evidence of a kind of symbiosis between Sogdians and Turks after the latter had become masters of the steppe in the 6th century. Soon after the Turkish overthrow of the Hephthalites a Sogdian named Maniach was sent first to Persia and then to Byzantium to open up the silk trade, and other Sogdians played a prominent role in diplomatic relations between the Turks and the Chinese (Chavannes, 1903, pp. 234-35).

Sogdians connected with the Turks were influential during the transition between Sui and T’ang. In one Chinese source (T’ung-tien 197.6a, cited in Pulleyblank, 1952, pp. 347-54) a group associated with the northern Turks was identified as che-chieh (zhe-jie), probably a transcription of Persian čākar (q.v.) “servant,” a term that also had the special sense “warrior” because of its application to elite troops employed as a ruler’s bodyguard; this group established itself at Hami and Lop Nor, straddling the eastern ends of both branches of the Silk Road. It maintained a semi-independent status until its surrender to T’ang in 630 (Chavannes, 1903, p. 313; Pulleyblank, 1952, pp. 347-54). There are also approximately contemporary references to a distinct Hu, that is, Sogdian, “tribe” that wielded great influence at the court of the northern Turkish ruler Hsieh-li Qaghan in Mongolia. These Hu were said to be “grasping and presumptuous, and vacillating by nature” and were accused of inducing the ruler to multiply laws and regulations and to engage in constant warfare, which caused disaffection among his own Turkish subjects and contributed to his overthrow by T’ang in 630 (Pulleyblank, 1952, p. 323). The Sogdian component among the northern Turks did not disappear after this event. It settled in the Ordos region, within the bend of the Yellow river, where in 679 a special administrative arrangement, Six Hu Prefectures, was established by the T’ang government. This name continued to refer to the descendants of these Sogdians for the next hundred years, long after the specific administrative unit had disappeared. Members of this group, recognizable by their “Sogdian” surnames, were mentioned frequently, both collectively and as individuals, in historical sources and sometimes played important roles in historical events (Onogawa; Pulleyblank, 1952). An Lu-shan, who rose through service in the Chinese army to become military governor of a large sector of the northern frontier and in 755 led a revolt that nearly overthrew the dynasty (Pulleyblank, 1955, passim), was the son of a Sogdian father and a Turkish mother and probably came from this group. His name can be identified as Iranian *Rōxšan (Pulleyblank, 1955, p. 15).

![]()

A Chinese Qi depiction of Soghdians (Picture and caption from Kaveh Farrokh’’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division and were also presented at Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006).

The descendants of the Hu of the Six Prefectures can be traced even later in history (Pulleyblank, 1952, pp. 341ff.; Onogawa). In 786 a Tibetan invasion of the Ordos region forced them to move to northern Shansi, where they were joined by the Sha-t’o (Shatuo) Turks. In the last quarter of the 9th century they formed a distinct component of the Three Tribes of the Sha-t’o, which played an important part in the civil wars at the end of the T’ang dynasty and in the following Five Dynasties period (907-60). The surname of the founder of Later Chin (936-41), Shih Ching-t’ang (Shi Jingtang), who came from the Sha-t’o confederacy, reveals his Sogdian ancestry; several of his female ancestors also had Sogdian surnames (Pulleyblank, 1952, pp. 341ff.; Onogawa, pp. 979-80).

It must be acknowledged that in the long history of the Hu of the Six Prefectures there is little evidence of direct connections with their Sogdian homeland or with mercantile activities. Living in the grasslands of the northern Chinese frontier, they seem to have adopted the way of life of their Turkish neighbors, with whom they frequently intermarried, and it is as mounted warriors that they are usually mentioned in the sources. The role of Sogdians as cultural intermediaries between the nomads and their settled neighbors and promoters of mercantile interests among the nomads became prominent once more, however, when the Uighurs succeeded the T’u-chüeh Turks as masters of the steppe in the 8th and 9th centuries. The Uighurs’ adoption of the Manichean religion (see below) and the privileged position that they enjoyed because of their assistance in restoring the T’ang dynasty after the An Lu-shan rebellion (Mackerras, 1972, p. 37) provided distinct advantages for Sogdian merchants under their protection. It is reasonable to assume, too, that the Uighurs’ gradual acculturation to their Sogdian subjects during this period had much to do with their adoption of settled life in the oases of Kansu and Sinkiang after the collapse of their steppe empire.

Persians in the China Sea trade

Although details remain controversial, there is clear evidence that sea trade between China and India and points farther west began about the end of the 1st century b.c.e. The arrival by sea of envoys to the Later Han dynasty from India was recorded in 159 and 161; in 166 an envoy was reported to have come from “King An-tun (An-dun) of Ta-ch’in (Da-qin),” that is, presumably, the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Chavannes, 1907, p. 185). The claim of this “envoy” to such credentials is unlikely to have been genuine, but his arrival is evidence that by 166 the sea route was known as an alternative to the overland route through Parthia. In 226 a merchant from Ta-ch’in arrived in Tongking and was sent to the court of Wu, then an independent kingdom with its capital at Nanking (222-58), where he was questioned by the ruler (Wolters, p. 42). Wu, like later Chinese kingdoms south of the Yangtze, had a special interest in maritime communications with the south and west and dispatched a mission that brought back valuable information about India and Ta-ch’in, as well as Southeast Asia. One of these envoys was K’ang T’ai (Kang Tai), very likely a Sogdian expert on foreign trade who had come to Wu from northern China. Unfortunately, only fragments of the written records that he left survive (Wolters, pp. 42, 271 n. 63, with references to discussion of the date by Pelliot, Hsiang Ta, and Sugimoto).

Persia is not mentioned directly in these sporadic early Chinese references to sea trade with the west. In the 5th and 6th centuries, for which evidence of regular commerce via the south China Sea is more abundant, Persian goods played a major role, and the epithet Po-ssu (Persian) was even sometimes applied to non-Persian products that came to China from the west. Opinions have differed, however, about whether or to what extent Persian traders came to Chinese ports (Wang, pp. 59-61; Wolters, pp. 139ff.). There is good evidence that in the T’ang period Persian, and later Arab, ships frequently visited Hanoi and Canton and that many Persians and Arabs were settled in those cities (Wang, pp. 79-80; Schafer, 1963, p. 15). Before the T’ang period, however, it seems that the eastern end of the trade was in the hands of Indonesians and that Ceylon was the point at which Chinese products destined for the west and Persian products destined for China were exchanged (Wang, pp. 60-61; Wolters. pp. 146ff.).

Iranians and religion in China: Buddhism

In the 2nd century c.e. the Kushan empire was the main center from which missionaries carried Buddhism to China, and naturally Iranians played a notable part in this activity. An Shih-kao (q.v.; An Shi-gao), who arrived in China in 148 c.e. and became the first translator of Buddhist sutras into Chinese, was a Parthian prince. Another early translator, An Hsüan (Xuan), was originally a Parthian merchant who arrived and settled in Lo-yang in 181 (Zürcher, I, p. 23). The surnames Chih (from Yüeh-chih) and K’ang (see above) were especially frequent among westerners involved in translation activities in the 2nd and 3rd centuries. It is probable that by that time they no longer referred to specific nomadic groups but more generally to the predominantly Iranian populations of Afghanistan and western Turkestan respectively. Beside first-generation immigrants like An Shih-kao and An Hsüan, Iranian Buddhists included men like K’ang Seng-hui, the son of a Sogdian merchant living at Chiao-chih (Jiao-zhi; Hanoi) in the extreme south of China, and Chih Ch’ien, whose grandfather had come to China with several hundred fellow countrymen in the time of the Han emperor Ling (168-90; Zürcher, I, p. 23). Indians, who bore the surname Chu (Zhu), from T’ien-chu (Tian-zhu, Mathews, nos. 6361, 1374, the name for India in the Han period, based on a transcription of Old Iranian *Hinduka; Pulleyblank, 1962, p. 117), very likely also traveled primarily from or by way of the Kushan empire.

Probably at the same period missionaries from Kushan established Buddhism in the oases of the Tarim basin, providing a congenial corridor of communication for Buddhist pilgrims going from China to India “in search of the law” (Brough; Zürcher, I, pp. 59ff.). The first known example of such a quest is that of the Chinese monk Chu Shih-hsing (Zhu Shi-xing, written with a character [Mathews, no. 1346] different from that in T’ien-chu), who set out in 260 or a few years later and traveled as far as Khotan, where he succeeded in obtaining the particular text that he sought (Zürcher, I, pp. 61-63). Khotan remained a flourishing Buddhist center and an important way station on the route to India until the Muslim conquest (ca. 1006).

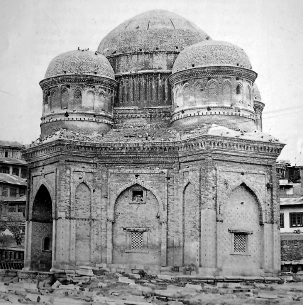

![]()

Tang Chinese nobles engaged in the Iranian game of polo (right). Interestingly a Chinese princess by the name of Yang Kwei-Fei popularized the game among Chinese women after her contacts and friendship with Iranian noblewomen who had settled in the Chinese metropolis of Chang’ An (Picture and caption from Kaveh Farrokh’’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division and were also presented at Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006).

Chinese Buddhist pilgrims were, of course, primarily interested in the Indian sources of their religion, rather than in the Iranian lands through which they passed, but their travel accounts nevertheless contain much incidental information about the eastern portion of the Iranian world. The most important from this point of view are the reports of Fa-hsien (Fa-xian, 399-412), who spent some time in Khotan before traveling south to India; Sung Yün (Song-yun, 518-22), who, accompanied by the monk Hui-sheng, undertook a mission to the Hephthalite capital in Bactria; and Hsüan Tsang, who traveled through the Tarim basin by the northern route to the territory of the western Turks, then south through Afghanistan to India, and returned via Khotan on the southern route. His Ta T’ang Hsi-yü chi (Da Tang Xi-yu ji (record of the western regions in Great T’ang) is a valuable firsthand account of conditions in those regions in the first half of the 7th century (Beal; Waley, pp. 23-29).

Mazdaism

Mazdaism, or Zoroastrianism, the official religion of the Sasanian empire, seems to have arrived in China early in the 6th century, probably as a result of diplomatic contacts with Persia. In China it came to be known as Hsien (Xian; Mathews, no. 2657, Early Middle Chinese xen), written with a graph that is rarely found in any other context and has given rise to a good deal of puzzlement (cf. Pulleyblank, 1962, p. 117); it is, in fact, simply a way of writing an old dialect pronunciation of Chinese t’ien (tian; Mathews, no. 6361) “heaven.” T’ien “heaven” or t’ien-shen “heaven god” was the Chinese Buddhist equivalent for Sanskrit deva “god,” and there is also evidence for the variant pronunciation hsien in Buddhist usage. Application of the Buddhist term deva to the god of the Persians was a natural extension. The more specific terms huo-shen “fire god” and huo-hsien “fire deva” are also found. In the Shih ming (written ca. 200 c.e.) the pronunciation of the word for “heaven” with initial x, rather than t’, was said to be characteristic of the central provinces, including the two Han capitals, Ch’ang-an and Lo-yang, whereas the pronunciation with tδ was associated with the eastern seaboard (Bodman, p. 28). In the 6th century it seems that pronunciation with x was confined to the “land within the passes” (Dien, citing Hui-lin, p. 550c), that is, the Ch’ang-an region, which by then had declined to a provincial backwater. What is not clear is why the word was always pronounced in this special way when applied to Zoroastrianism, even after Ch’ang-an had once again become the capital, under the Sui and T’ang dynasties, and had lost this local peculiarity.

In the later 6th century Zoroastrianism attained a degree of official recognition in northern China, a status that it retained in the Sui and T’ang periods. There are known to have been four temples in Ch’ang-an, two in Lo-yang, and others in K’ai-feng and in cities along the road to the northwest (Ch’en). The foreigners in charge of them, known by the non-Chinese term sa-fu or sa-pao (sabao), had Chinese official rank (Pelliot,1903). In Northern Ch’i and Sui they were subordinate to the hung-lu-ssu (honglusi), the office in charge of receiving foreign tributary missions, but in T’ang they were attached to the bureau of sacrifices, a division of the board of rites. It is likely that the worshipers were all or mainly foreigners resident in China. Anecdotal literature reveals that the Chinese were interested in the ritual dancing that took place (see dance i) and associated the temples with feats of conjuring. Mazdaism was one of the foreign religions proscribed in 845, but there are a few references to Zoroastrian temples as late as the 12th century.

Nestorian Christianity

Christianity (q.v.) in its Nestorian form was officially introduced in China in 638, when a Persian monk, A-lo-pen (Aluoben), presented scriptures to the T’ang court; as a consequence the government issued a decree ordering construction of a monastery for twenty-one monks in the I-ning (Yi-ning) ward in northwestern Ch’ang-an (Moule, pp. 39ff.). It seems that at first it was called Po-ssu (Persian) monastery, for, according to another decree, issued in 745 (Moule, p. 67), it had been learned that Christianity had originated, not in Po-ssu, but in Ta-ch’in (the Roman empire); the name was thus changed to Ta-ch’in monastery. A corresponding name change was ordered for a similar monastery in Lo-yang and for others in prefectural cities throughout the empire. In addition to these brief data from T’ang historical sources, the famous Nestorian stone inscription in Chinese and Syriac, dated 781 and probably from one of the monasteries in or near Ch’ang-an, was rediscovered early in the 17th century; it had probably lain buried since the suppression of foreign religions in 845 (Moule, pp. 27-52). Further evidence for the existence of Christianity with an Iranian background in T’ang China can be found in Christian texts discovered at Tun-huang, as well as in scattered references in other sources. It seems likely that, like Mazdaism, Nestorian Christianity was largely confined to the foreign community and had little impact on the general population. Christians were among the foreigners massacred when the Huang Ch’ao rebels sacked Canton in 878 (Moule, p. 76). Thereafter Christianity disappeared from China until it was reintroduced under the Mongols.

Manicheism

Manicheism (See chinese turkestan ix. manicheism in central asia and chinese turkestan) was mentioned by Hsüan-tsang in his account of Persia (Ta T’ang hsi-yü chi 11.938a; Chavannes and Pelliot, 1913, p. 150). It, too, arrived in China in the 7th century. In 694 a Persian, Fu-to-tan Fu-duo-dan = Aftādān “episcopus”), was received by Empress Wu and presented her with a Manichean treatise (Chavannes and Pelliot, 1913, pp. 152-53; Lieu, p. 189); in 719 a Manichean astronomer arrived with a letter of recommendation from a local ruler in Ṭoḵārestān and a request to be allowed to found a church (Lieu, p. 188). Manicheans may have had more interest than Mazdeans (and perhaps also Persian Nestorians) in propagating their faith, for in 732 it was deemed necessary to issue a decree declaring that, though Manicheism was a false doctrine masquerading as Buddhism, it was permissible for Iranians (Hu) from the west to continue to practice it (Lieu, p. 190). That some Manicheans were astronomers is of particular interest because the Iranian seven-day week, with days named after planets, became known in China at about the same time (see viii, below; calendars i). The Chinese Manichean name for Sunday, Mi (< Middle Chinese Mjit < Sogdian Mīr), is marked in red on a Chinese calendar from Tun-huang (facs. in Pelliot and Haneda), a practice that survived in popular almanacs in southern China at least until the end of the 19th century (Chavannes and Pelliot, pp. 158-77).

![]()

Manichean Painting (9th century CE) at the Shotcho Cave (Picture and caption from Kaveh Farrokh’’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division and were also presented at Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006).

The great opportunity for Manicheism in China came in 762, when the Uighur qaḡan became a convert at Lo-yang, which he had captured and sacked during the restoration of the T’ang dynasty after An Lu-shan’s rebellion. When he returned to Mongolia the qaḡan made Manicheism the state religion. As the T’ang were indebted to the Uighurs, the latter were able to demand the establishment of Manichean temples not only in Ch’ang-an and Lo-yang but also in T’ai-yüan and various localities in the Yangtze region (Chavannes and Pelliot, pp. 261-62; Lieu, p. 194). Uighur support for Manicheism in such places was no doubt for the sake of the Sogdian (Hu) merchants settled there and in contact with Manichean Sogdians at the Uighur court.

The collapse of the Uighur empire after the defeat by the Kirghiz in 840 deprived the Manicheans of their protection (Chavannes and Pelliot, pp. 284ff.). In China the first attack came in 842, when temples in the Yangtze region were abolished (Chavannes and Pelliot, p. 293). In the following year the Manichean religion was proscribed throughout the empire (Chavannes and Pelliot, pp. 293-95; Lieu, p. 196). The temples and all their property were confiscated, scriptures were publicly burned, and the clergy were ordered to return to lay life and, in some instances at least, executed or exiled to the frontiers with other Uighurs. This sequence of events was followed two years later by a more general persecution of foreign religions, including Buddhism (Lieu, p. 198), though by that time it had become so thoroughly assimilated into Chinese life that it eventually recovered its former position.

![]()

The 3rd century CE Iranian prophet Mani as depcited in a Chinese temple carving in Dunhuang Picture and caption from Kaveh Farrokh’’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Divisionand were also presented at Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006).

Although Manicheism disappeared as an officially recognized cult, it must, unlike Nestorianism and Mazdaism, have struck roots among the Chinese population, for it survived as an underground sect for nearly 800 years in the southeast coastal region of Fukien. The hostility of both the government, which looked with suspicion on all popular religious movements as seedbeds of subversion, and the Buddhists, who regarded Manicheism as a pernicious heresy, dominates the scant Chinese literary references to the “religion of light” and has sometimes unduly influenced modern scholars. Manicheism has thus been counted as one of the sects involved in popular uprisings under the Sung (960-1127) and at the end of the Yüan (1206-1368; see iii, below). The modern historian Wu Han even developed the theory, which has been quite widely accepted, that there was a Manichean element in the ideology of the Red Turban rebels, a Buddhist Maitreya sect to which Chu Yüan-chang (Zhu Yuan-zhang), the founder of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), originally belonged (Wu Han). More recent scholarship has shown, however, that the ascetic and peaceful Manicheans of Fukien had nothing to do with the Red Turbans (cf. Lieu, pp. 259-61). The coincidence in name between the “religion of light” and the Ming dynasty (“dynasty of light”) had unfortunate consequences for the Manicheans, however; having allegedly usurped the dynastic title, they became a special target for persecution (Pelliot, 1923, pp. 206-07). Nevertheless, small pockets survived to around 1600, after which the records are silent (Lieu, p. 263).

Bibliography

P. Aalto, “The Name of Tashkent,” Central Asiatic Journal 21, 1977, pp. 193-98.

S. Beal, Si-yu-ki. Buddhist Records of the Western World. Translated from the Chinese of Hiuen Tsiang (A.D. 629), 2 vols. in 1, London, n.d. (contains translations of the accounts of Fa-hsien and Sung Yün).

A. D. H. Bivar, “The History of Eastern Iran,” in Camb. Hist. Iran III/1, pp. 181-231.

N. C. Bodman, A Linguistic Study of the Shih Ming, Harvard-Yenching Institute Studies 11, Cambridge, Mass., 1954.

J. Brough, “Comments on Third-Century Shan-shan and the History of Buddhism,” BSOAS 28, 1965, pp. 582-612.

E. Chavannes, Documents sur les Tou-kiue (Turcs) occidentaux, Paris, 1903.

Idem, “Les pays d’Occident d’après le Heou Han chou,” T’oung Pao 8, 1907, pp. 149-235.

Idem and P. Pelliot, “Un traité manichéen retrouvé en Chine,” JA, Nov.-Dec. 1911, pp. 499-617; Jan.-Feb. 1913, pp. 99-199, Mar.-Apr. 1913, pp. 261-395.

Ch’en Yüan, “Huo-hsien chiao ju Chung-kuo k’ao,” Kuo-hsüeh chi-k’an 1, 1923, pp. 27-46. Chiu T’ang shu, compiled by Liu Hsü (887-946), Peking, 1975.

A. E. Dien, “A Note on Hsien “Zoroastrianism,”” Oriens 10, 1957, pp. 284-88. I. Ecsedy, “Early Persian Envoys in Chinese Courts,” in J. Harmatta, ed., Studies in the Sources on the History of Pre-Islamic Central Asia, Budapest, 1979, pp. 153-62 (= Acta Antiqua Academiae Scientarum Hungaricae 25, 1977, pp. 227-36).

R. N. Frye, The History of Ancient Iran, Handbuch der Altertumswissenschat III/7, Munich, 1984.

Aomi-no Mabito Genkai, “Le voyage de Kanshin en orient (742-754),” tr. J. Takakusu, Bulletin de l’Ecole Française d’Extrême-Orient 28, 1928, pp. 3-41, 441-72; 29, 1929, pp. 47-62.

F. Grenet and N. Sims-Williams, “The Historical Context of the Sogdian Ancient Letters,” in Transition Periods in Iranian History. Actes du symposium de Fribourg-en-Brisgau (22-24 mai 1985), Studia Iranica, cahier 5, 1987, pp. 101-22.

J. Harmatta, “Sino-Iranica,” Acta Antiqua Academiae Scientarum Hungaricae 19, 1971, pp. 113-43.

Idem, “Sogdian Sources for the History of Pre-Islamic Central Asia,” in J. Harmatta, ed., Prolegomena to the Sources on the History of Pre-Islamic Central Asia, Budapest, 1979, pp. 153-55.

W. B. Henning, “The Date of the Sogdian Ancient Letters,” BSOAS 12, 1948, pp. 601-15.

Hsia Nai, “Tsung-shu Chung-kuo ch’u-t’u ti Po-ssu Sa-san ch’ao yin-pi” (A survey of Sasanian silver coins found in China), K’ao-ku hsüeh-pao, 1974, pp. 91-110 (with English summary).

Hsiang Ta, T’ang tai Ch’ang-an yü hsi-yü wen-ming (Ch’ang-an of the T’ang dynasty and the culture of the western regions), enl. ed., Peking, 1957. Hsin T’ang shu, compiled by Ou-yang Hsiu (1007-72), Peking, 1975.

Hui-lin (comp. 810), Yi-ch’ieh-ching yin-i (Sounds and meanings of the complete canon), in Taishō shinshu daizōkyō LIV, Tokyo, 1928.

S. N. C. Lieu, Manichaeism in the Later Roman Empire and Medieval China. A Historical Survey, Manchester, 1985.

Liu Ts’un-Yan, “Traces of Zoroastrian and Manichaean Activities in Pre-T’ang China,” in P. Demiéville,Selected Papers from the Hall of Harmonious Wind, Leiden, 1976, pp. 3-55.

C. Mackerras, The Uighur Empire According to the T’ang Dynastic Histories, Canberra, 1972.

B. J. Mansvelt Beck, “The Fall of Han,” in D. Twitchett and M. Loewe, eds., The Cambridge History of ChinaI: The Chin and Han Empires 221 B.C.-A.D. 220, Cambridge, 1986, pp. 317-76.

H. Maspéro, La Chine antique, new ed., Paris, 1955. R. H. Mathews, Mathews’ Chinese English Dictionary, rev. ed., Cambridge Mass., 1943.

R. A. Miller, Accounts of Western Nations in the History of the Northern Chou Dynasty, Chinese Dynastic Histories Translations 6, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1959.

A. C. Moule, Christians in China before the Year 1550, London, 1930.

K. Nakamura, “Tōdai no Kanton,” Shigaku zasshi 28, 1917, pp. 242-58, 348-68, 487-95, 552-76.

Idem, “Kanton no shōko oyobi Kanton Chōan wo renketsu suru suiro shōun no kōtsu,” Tōyō gakuhō 10, 1920, pp. 244-66. Nan shih, compiled by Li Yenshou (d. before 679), Peking, 1975.

H. Onogawa, “Kakyoku Rikuchō Ko no enkaku” (The history of the Hu of the Six Prefectures), Tōa jimbun gakuhō 1, 1942, pp. 957-90. Pei shih, compiled by Li Yen-shou (d. before 679), Peking, 1974.

P. Pelliot, “Le Sa-pao,” Bulletin de l’Ecole Française d’Extrême-Orient 3, 1903, pp. 665-71.

Idem, “Les influences iraniennes en Asie centrale et en Extrême-Orient,” Revue d’histoire et de littérature religieuses, N.S. 3, 1912, pp. 97-119.

Idem, “Les traditions manichéennes au Foukien,” T’oung Pao 22, 1923, pp. 193-208. Idem and T. Haneda, eds., Tun-huang i-shu, Shanghai, 1926.

E. G. Pulleyblank, “A Sogdian Colony in Inner Mongolia,” T’oung Pao 41, 1952, pp. 319-52.

Idem, The Background of the Rebellion of An Lu-shan, London, 1955.

Idem, “The Consonantal System of Old Chinese,” Asia Major 9, 1962, pp. 58-144, 206-65.

Idem, “Chinese and Indo-Europeans,” JRAS, 1966, pp. 9-39.

Idem, “Chinese Evidence for the Date of Kaniska,” in A. L. Basham, ed., Papers on the Date of Kaniska, Leiden, 1969.

E. H. Schafer, “Iranian Merchants in T’ang Dynasty Tales,” in Semitic and Oriental Studies Presented to William Popper, University of California Publications in Semitic Philology 11, 1951, pp. 403-22.

Idem, The Golden Peaches of Samarkand, Berkeley, 1963. Sui shu, compiled by Wei Ch’eng (580-643), Peking, 1973.

J. Takakusu, A Record of the Buddhist Religion as Practised in India and the Malay Archipelago (A.D. 671-695) by I-tsing, Oxford, 1896. T’ang Ch’ang-ju, Wei Chin Nan-pei ch’ao shih lun-ts’ung (Studies on the history of Wei Chin and the northern and southern dynasties), Peking, 1955.

A. Waley, The Real Tripitaka, London, 1952. Wang Gungwu, “The Nanhai Trade. A Study of the Early History of Chinese Trade in the South China Sea,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 31/2, 1958, pp. 1-135.

Wei shu compiled by Wei Su (506-72), Peking, 1974.

O. W. Wolters, Early Indonesian Commerce, Ithaca, N.Y., 1967.

Yü Ying-shih, Trade and Expansion in Han China, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1967.

Wu Han, “Ming-chiao yü ta Ming ti-kuo,” Ch’ing-hua hsüeh-pao 13, 1941, pp. 49-85; repr. in idem, Tu shih cha-chi, Peking, 1956, pp. 235-70.

E. Zürcher, The Buddhist Conquest of China, 2 vols., Leiden, 1959.

A Tajik lady in a bazaar in Dushanbe displaying the local brand of Persian bread known as “Kulcha” (Photo:

A Tajik lady in a bazaar in Dushanbe displaying the local brand of Persian bread known as “Kulcha” (Photo: